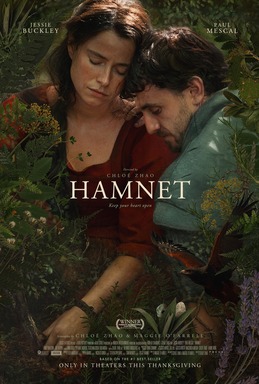

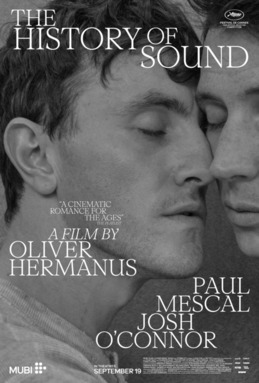

Release Date – 23rd January 2026, Cert – 15, Run-time – 2 hours 8 minutes, Director – Oliver Hermanus

World War I, two music students (Paul Mescal, Josh O’Connor) find their relationship defined by folk music they share and archive, even as the war and years separates them.

The History Of Sound isn’t an 8am film. Especially 8am in the final two days of a film festival. It’s a film that certainly needs time and attention as it itself takes its time with slow pacing, charting the years that pass by – and the distance that increases – between main character Lionel (Paul Mescal) and lover David (Josh O’Connor). The pair’s relationship starts as music students at university, leading them to recording and archiving folk music across America before the war leads to multiple separations between them over the passing years.

Mescal and O’Connor are fantastic together. Gently commanding each scene they appear in together. A musical introduction at a bar piano sets off a sensual bond formed through song. While the opening stages, and indeed marketing, may place this as a two-hander between the pair it’s undoubtedly led by Mescal with O’Connor really not being in this as much as you might expect. It’s his character’s life that we hear of having changed over the years while we actually see that of Lionel’s playing out.

The film’s basis, and depiction of music in the lives of the characters, is summed up rather nicely in the closing stages. Chris Cooper briefly crops up to tell us about “stories with sadness so great they return to songs.” There’s a feeling of melancholy throughout the film which is almost rounded off with this phrase, a reflective sadness from Mescal’s Lionel as he seems to look back on his life, constantly thinking about David, and the music that brought them together in the first place. There’s a clear sadness pushed in the folk music we hear throughout, emphasising the slow and reflective nature of the film. As if something has been lost even before the relationship has started.

That feeling of loss carries over once the pair are distance by the war, however that also comes in the form of losing O’Connor’s presence for good chunks of time. The film is at its best when he and Mescal share the screen, creating an engaging style and intimacy in the conversations their characters have. It means that there’s more interest in their bond together than when largely focusing on one – despite the continued strength of the respective performances, particularly Mescal who acts as lead with O’Connor very much being support.

Particularly when distanced Lionel’s longing emphasises the slow pacing that runs throughout the just over two-hour run-time. The knock-on effect of everything coming together is a slightly overlong feeling to the film with just how slow it is, and especially the strongest elements being somewhat far apart (even if intentionally so). It just makes us, like the central character, wish for O’Connor’s return, largely for that added spark that helps see things through.

While Mescal and O’Connor are both on great form in The Sound Of History it’s particularly when sharing the screen together, when distanced the slightly-too-slow pacing is highlighted and while watchable there feels something missing to really maintain full engagement.